Cass Corridor Culture

Cass Corridor Culture: In and Around Wayne State, 1960s - 1980s

David Adamany Undergraduate Library, Third Floor

Gullen Mall, Detroit

This permanent exhibition highlights the work of artists, poets and musicians, many of whom lived and worked in 'the Corridor' during those years. The counterculture of the 1960s and `70s had its roots on college and university campuses, including WSU, where artists, musicians, poets and writers developed a strong and vibrant creative community. This display features some of the most iconic art created by artists of the Cass Corridor, including works by Jim Chatelain, John Egner, Brenda Goodman, Bradley Jones, Ann Mikolowski, Gordon Newton and The Alternative Press.

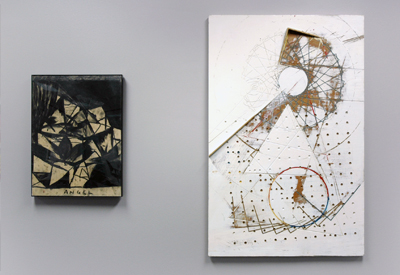

Gordon Newton, Angel, 1971; Paul Schwarz, Untitled (Setup II), 1977

Gordon Newton, Wheel of Fortune, 1976

Jim Chatelain, Jim's Baloney, 1972; Brenda Goodman, Untitled 8, A Song For My Mother, 1995

MC5, 'Kick Out the Jams' single with selected music ephemera.

Art and the Industrial City

by Dora Apel, Ph.D., W. Hawkins Ferry chair in Modern & Contemporary Art History

Wayne State University

As an admirer of American industry, Diego Rivera offered Detroit a utopian view of itself at the height of the Depression in the famous murals he completed at the Detroit Institute of Arts in 1933. Finding inspiration in industry, its raw materials and the workers who made it run, Rivera pictured labor and management working in a necessary harmony for the greater cosmic good at a time when layoffs, strikes, and unemployment wracked the city and the country at large.[i] In the restless 1960s and 70s, when explosive social and political movements unsettled the nation yet again, a dynamic group of Detroit artists emerged in the midst of another set of uneasy conditions. But uneasiness can be a motor force in Detroit. How did the pressures of poverty, industry and race affect artistic production in these circumstances? Was it possible to use the raw material of the city's anxieties to offer it a different, hopeful view of itself?

Rejecting the values of postwar middle-class society, alternate-culture movements sprang up around the country, not least in Detroit, with their own lifestyles, often supported by a burgeoning drug culture, political protests, underground newspapers, music, literature and art. The counterculture of the sixties and seventies had its roots on college and university campuses, including Wayne State University and the Center for Creative Studies (Detroit Society of Arts and Crafts until 1974). Opposition to the Vietnam War, to poverty and injustice, to the strictures of bourgeois morality and the nuclear family all fueled the counterculture, which thrived on the rhetoric of "cultural revolution."

It is no accident that the Cass Corridor phenomenon occurred during a time when the younger generations were attempting to reinvent politics, culture, and morality in America in a politically-charged era that included the assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X, the rise of drug-guru Timothy Leary, the imagery of war in Viet Nam on nightly television, and the killings at Kent State University. Following the anticommunist witchhunts of the McCarthy era, the Civil Rights struggles of the fifties and sixties, and the disillusionment with conformist suburban mythologies, the powerful sense of community established in the Cass Corridor produced an explosive synergistic energy and intense creative flowering.

The volatility of race relations that shook the country also had a profound effect on Detroit, then the nation's fifth largest metropolis and automaker to the country. Following the riots in Watts (1964) and Newark (1967), the most violent rebellion of all took place in July 1967 in Detroit. Deeply affected by the civil rights movement of the preceding two decades, the rioters, as historian Sidney Fine notes in his study of the Detroit riots, "signal[ed] to those in power that they must pay attention to the black ghetto and its problems." From this Fine draws a central insight: "In this sense, the rioting of 1967 was born of hope, not of despair, the hope that improvement would follow the disorder in the streets." [ii] Protest combined with hope characterized the 1960s even as the Detroit riots profoundly shook the complacency of the ruling elites and middle class. Art critic Marsha Miro observed, "If you survived those moments, when the whole fabric of urban living was in shreds and notions of law, order, justice and material abundance were in question, if you survived such confrontation, you sit forever uneasy." [iii] It can be argued, however, that uneasiness, combined with a belief in human agency and the need for progress, became a force for heightened awareness, deeper sensitivities, and cultural change during this turbulent era.

Bordering the campus of Wayne State University was a depressed inner city neighborhood bisected by Cass Avenue and known as the Cass Corridor. Its population included, by most estimates, some fifty to seventy-five artists working in buildings with studio complexes (such as Old Convention Hall, Common Ground and the Forsythe Building), storefronts, lofts, basements and apartments. Many of these artists were instructors, students or former students in Wayne State University's art department, and some were from the Center for Creative Studies. Social life centered on local gathering places and bars such as Cobb's Corner, whose owner Robert Cobb supported the local art scene and sometimes traded drinks for art. Cobb owned the Willis Gallery building (the Willis Gallery was a cooperative gallery established in a burned-out out furniture store), which became the primary exhibition venue for Cass Corridor artists, renting it out for years at reasonable rates, even trading rent for works of art. Cass Corridor artists developed a pride and affection for their area of the city, fostered by a shared sense of community and passion for artmaking.

After a visit to Detroit in 1978, art critic Robert Pincus-Witten commented on "the presence of a naked will to style, the conviction of young artists that they could make art out of a sheer desire to be artists." [iv] It was an attitude of unprecedented openness and self-invention. Without fame and fortune, everything could be risked. The abandonment of the city through accelerating white flight and business relocation meant that poor artists could rent big spaces to live and work cheaply and in close proximity, where they tried to create something of integrity with whatever means were available. "The lifestyles were intense," observed Corridor artist Gordon Newton. "What separated this certain group of people was intensity and maintaining it. It builds in you, like your muscles if you were working out. We were bouncing off each other." [v]

The most comprehensive history of the Cass Corridor artists and other area cultural efflorescences was written in the 1980 exhibition catalog Kick Out the Jams: Detroit's Cass Corridor, 1963-1977. [vi] The Kick Out the Jams exhibition, which included twenty-two artists, was co-organized by curators Mary Jane Jacob and Jay Belloli at the Detroit Institute of Arts. [vii] In the catalog, Jacob traced the evolution of the movement through the "Wagstaff Years" of DIA Curator of Contemporary Art Samuel J. Wagstaff, Jr. (1968-1971) and the formative era of the Willis Gallery in the years 1971-77. Jacob credits Wagstaff with recognizing the tremendous energy and vitality of Cass Corridor art and with acting as a liaison between the artists and the larger art world in a way that served to stimulate the local art scene to new levels of productivity and exchange.

Wagstaff updated the contemporary art collection at the DIA with works by influential conceptual artists, some of whom used scrap materials in dynamic ways that inspired and resonated with the work of Cass Corridor artists. He organized exhibitions in Detroit of work by minimalist, conceptual, and earthworks artists such as Robert Morris, Michael Heizer, Carl Andre, Lynda Benglis, Walter de Maria, Hans Haacke, Eva Hesse, Richard Tuttle, and William Wegman, among others. He also initiated the purchase and installation of Tony Smith's Gracehoper on the grounds of the DIA, organized trips to New York for collectors and friends of the museum, supported counterculture events, such as the staging of the play Hair, and particularly championed the work of Gordon Newton.

It was during the years of the Willis Gallery that a small but devoted group of Detroit collectors began to frequent the gallery exhibitions, James F. Duffy, Jr. significant among them. Duffy, who owned a business that distributed industrial pipes and pipefittings, saw a unique opportunity to acquire art by artists whom he could meet and get to know. The relationship between the artists and James Duffy was made remarkable by Duffy's commissioning and installation of Cass Corridor art in his warehouse on West Jefferson Avenue, in what became a kind of industrial museum of art. Reflecting on this phenomenon, Mary Jane Jacob wrote:

Duffy had the means, facilities, and foresight to not only regularly buy the work of a sizeable group of artists, but also to commission pieces for his apartment, office, and warehouse. The Duffy warehouse complex certainly stands as a most significant and unique approach to art patronage. In this industrial setting, where one would not expect to find art, artists encountered a sympathetic and intriguing environment for their work. Visiting the warehouse today, one comes upon works of art attached to workbenches, nailed to walls or cabinets, hanging from the ceiling, painted on doors and exterior and interior surfaces. Virtually filling the space, they remain unobtrusive, often not even visible at first, blending as they do so perfectly with the environment. . . . Ironically, or perhaps appropriately, Duffy's warehouse has become a kind of museum-in-life of Cass Corridor art from around 1973 to the present. [viii]

Duffy's warehouse and office thus served as a unique forum for the exhibition of works by artists in the Cass Corridor and those who came later, just as the proximity of Wayne State University, Center for Creative Studies, and the Detroit Institute of Arts served as a fertile ground for the development of the Cass Corridor art community in the first place.

When a 1975 exhibition organized by Diana Aceti (one of the Willis Gallery directors) at the plush Somerset Mall in suburban Troy brought works by fourteen artists to a new audience, Marsha Miro observed, "The works in the exhibit will be something of a surprise to some," explaining that "the art, which plunges into the raw commercial wastelands of the city, is a product of Detroit's most successful unstructured art communitya cadre of artists living in what might politely be called adverse conditions, held together by the paste of common purpose: a free-wheeling, unbounded fizzbang approach to art and all its mediums." [ix]

The Cass Corridor "aesthetic" has come to be thought of as raw, gritty, and seemingly unrefined, with a reliance on found industrial objects. A distinctly urban aesthetic has become the legacy and influence of the movement, which includes artists such as Gordon Newton, Michael Luchs, Bob Sestok, John Egner, Jim Chatelain, Ellen Phelan, Nancy Pletos, Nancy Mitchnick, Brenda Goodman, John Piet, Paul Schwarz and Doug James. In large part this is true because two of the artists who worked this way, Gordon Newton and Michael Luchs, came to be considered the seminal Cass Corridor artists. While Newton often used drills and saws, Luchs sometimes burned and shot at his materials. Producing a kind of troubling energy and excitement, this aggressive approach seemed to capture the contradictions of a city on the edge, in a nation on the verge of chaos. Dubbed "rough," "tough," and "urban expressionism" by art critics, this work seemed to express the stark and dangerous side of inner city existence, reproducing the appearance of violence in the artmaking itself. Michael Luch's signature representations of rabbits, either caged or not, evoke a pent-up, frenetic energy, or sense of lethal entrapment. Rabbits have a long history of symbolic association with speed, fear, anarchy, and reproduction, making them peculiarly apt emblems for the cars, crime, and assembly line of the industrialized city.

But the legacy of a heavy reliance on found industrial objects is something of a myth, based on the "look" rather than the actual resources used. Materials such as the old fencing and chicken wire employed by Michael Luchs, for example, are associated more with the country than the industrial city. Most commonly, new materials were worked over until they appeared to be old industrial scraps and detritus. This might be understood as the response of young, white artists from varied backgrounds to the urban condition in which they found themselves. Artist John Egner, who joined the faculty at Wayne State University in 1966 and soon became an influential force in the emerging Cass Corridor art community, observes that Corridor artists "evoked and echoed the real physical reality of Cass Corridor lofts, alleys and apartments: woodwork that had been painted a hundred times; cracked or broken glass. This was the sad material of neglect and abandonment. Some Cass Corridor artists indulged in a crude form of faux antiquing." [x] Why embrace the abandoned and neglected? Young artists who staked their claim to this isolated part of the city in some sense sought to reclaim what others had forsaken while proclaiming their sophistication in the form of aesthetic "toughness." Recalls Egner, "Picasso was a god. Part of the art school/barroom rhetoric of the time, whether in New York or Detroit, was always toughness over decorative beauty. Picasso was better than Matisse because he was tougher. I heard that a million times. It was about being more manly." [xi]

The raw aesthetic of Cass Corridor art also seemed most in tune with the conceptual ideas and attitudes of artists such as Eva Hesse, Tony Smith, Mark di Suvero, and Robert Rauschenberg, who used unconventional materials and produced unorthodox assemblages. Cass Corridor artists made particular use of tools such as power saws and drills, and alternative materials such as bolts, aluminum paint, galvanized mesh and screening, cardboard, and duct tape. Art was understood to be about "process" as well as objects, and could result in a "purposeful anti-aesthetic, unbeautiful look." [xii] Perhaps such efforts might be better described as departures from the conventionally beautiful in the attempt to define a new aesthetic. Art critic Richard Armstrong astutely noted at the time of the Kick Out the Jams exhibition that the "tough, gritty" work revealed "an uncommon allegiance to the ideas of advanced abstraction. It is more in touch with its counterparts in downtown Manhattan than might be thought." [xiii] Corridor artists also used the DIA as their coffee shop and were always looking at diverse artistic expression, from the African, Egyptian, and Native American galleries to the works of the Abstract Expressionists. [xiv]

The "unbeautiful" look often came to characterize the work of Gordon Newton, which made a public splash in 1973 when the J.L. Hudson Gallery mounted a solo exhibition, described as "a sensational display of rough wooden pieces cut into with a circular saw and mounted vertically on the walls, as well as constructions of wooden molding, thickly varnished and stained dark abstract paintings, and debris (broken wood, torn plastic, and sawdust) arranged randomly in a pile with a network of strings overhead." [xv] Perhaps one of Newton's most emblematic pieces is Wheel of Fortune (1976), made for the Duffy Warehouse. Consisting of wood, cardboard, metal, paint, plaster, polyester resin, and other media, the work hung in the warehouse on the end of a long shelving rack made of slotted wooden crates stacked back to back and four high that were used to hold pipefittings. Wheel of Fortune, which evokesa huge constructed saw wheel, was mounted above the industrial products of Duffy's business. A photograph taken at the warehouse shows ten valve handles resting on the floor, their small wheels giving the impression of inoperable industrial scooters. The sculpture looming above these seemingly accidentally placed objects appears terrifying in its aggressive potential, as if threatening to slice down to size any sign of movement, like a butcher's blade descending into a tender cut of meat. The blade, however, is broken and incomplete, with jagged edges and sharp projections, and covered with a swirling mass of colored pigment. This wheel of fortune has run out of luck for those in its orbit. In the context of a city entering an economic recession, the deep pessimism of the broken wheel of fortune is surpassed only by its latent menace, which would be overwhelming were it whole.

Some contemporary observers of the Kick Out the Jams exhibition were critical of what they saw as a lack of direct reference to the issues of the city. Critic David Elliot wrote, "Poverty, crime, the mid-70s 'renaissance' led by the feds, auto magnates and Coleman Young, are just about invisible here. And would you guess that Detroit is preponderantly black? All of these artists are white." [xvi] But other critics recognized an inherently urban character to the nature of the work and the artists' working methods. Richard Armstrong, reviewing Kick Out the Jams for Art in America, characterized Newton's work as "quintessentially 'Detroit': brash yet elegant, beautiful reincarnations of cast-off materials, active, even frenzied urban creatures," while suggesting that Luchs "incorporates, even celebrates, decay in his work; he does this more markedly than Newton, but the appreciation of both artists for urban entropy and chaos is their most profound connection." [xvii]

Yet for Newton, who also regularly spent time in Northern Michigan and on the Great Lakes, decay was not an end in itself, but part of an organic process. In a rare interview, in reference to his works on diving boards and roller coasters, Newton observed, "None of it is a comment on industrial decay. There's a natural feel to these things. That's from my being outside, up north or on the lake, the way you feel in nature, the yearly cycle of growth and decaybut the decay nourishes the life." [xviii]

Perhaps the work of Cass Corridor artists in the sixties and seventies was not so much an industrial aesthetic as a post-industrial aesthetic. Reviewing an exhibition of work by twenty-one Detroit artists at Cranbrook Art Museum in 1979, Marsha Miro observed: "If anything, the art these Detroiters make is post-industrial, created as a negation of the notion that industrial progress means human progress. They pick up industry's pieces and mend them into a new existence as art that has no technological value." [xix] But what is the relation of this "new existence" to a failed promise of progress? Cass Corridor art seems an attempt to embody the latent power of industrial potential, even while recognizing its deterioration, which contributed to an era of strife and poverty.

If there are common factors in the diverse styles and methods of Cass Corridor artists, they include an exuberant drive toward new expression, a keen awareness of the larger artworld, and the emergence of something dark, edgy, and intense, not directly reflecting but connected in complex ways to both the personal and larger social, economic and political conditions in which these artists lived and worked. "The prevailing aesthetic was the idea that making art was a struggle, and every evidence of the struggle was beautifulscrapings, erasures, drips were all badges of courage." [xx] Like living in the city itself, artmaking was an aggressively hopeful gesture.

Today most of the Cass Corridor artists are still working, dispersed throughout the metropolitan Detroit area, New York, or elsewhere around the country. Many retain the dark core and uneasy edge of their early work. And the influence of Cass Corridor art can be felt in the labor of succeeding generations of artists, in a city that continues its prolific artistic traditions.

[i] For the most extensive discussion of the Detroit murals, see Linda Downs, The Detroit Industry Murals, New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1999.

[ii] Sidney Fine, Violence in the Model City: The Cavanagh Administration, Race Relations, and the Detroit Riot of 1967, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1989, 462. The riot lasted four days, and left 43 dead, 7,000 arrested, 1300 buildings destroyed, 2700 businesses looted, and damages of 22 million dollars. Some 4700 Army paratroopers and 1,500 National Guardsmen entered the city to quell the fighting and looting.

[iii] Marsha Miro, "Detroit: The Scrappiness of Survivors," DetroitFree Press, 2 December 1979.

[iv] Robert Pincus-Witten, "Detroit Notes: Islands in the Blight," Arts Magazine 52 (6 February 1978), 137.

[v] Quoted in John Barron, "Newton's Universe," Detroit Monthly (March 1988), 92.

[vi] Other groups, alternative galleries, workshops, and presses sprang up as spaces for experimental art, poetry, and music, starting with the Red Door Gallery, founded in 1963 by George Tysh and Carl and Sheila Schurer; Common Ground for the Arts founded in 1963; the Detroit Artists' Workshop and Artists' Workshop Press, founded in 1964 by John Sinclair and others (later renamed Trans-Love-Energies); Gallery 7, founded by Charles McGee in 1969 in a storefront across from Marygrove College, which became a center for black art and artists (McGee moved the gallery to the Fisher building and shifted emphasis to the experimental art of younger artists until the gallery closed in 1978); and the Alternative Press, founded in 1969 by Ken and Ann Mikolowski.

[vii] Artists included William Antonow, James Chatelain, James Crawford, Stan Dolega, John Egner, Georg Ettl, Steve Foust, Brenda Goodman, Jerry Hunt, Doug James, Bradley Jones, Aris Koutroulis, Michael Luchs, Nancy Mitchnick, Gordon Newton, Ellen Phelan, John Piet, Nancy Pletos, Paul Schwarz, Robert Sestok, Carol Steen, and Jonathan Waite.

[viii] Mary Jane Jacob,"Kick Out the Jams: The Emergence of a Detroit Avant-garde," Kick Out the Jams: Detroit's Cass Corridor 1963-1977 (Detroit Institute of Arts, 1980), 34.

[ix] Marsha Miro, "Inner City Style is Tough and Surprising," Detroit Free Press, 7 September 1975. Artists included Steve Foust, Nancy Pletos, Gordon Newton, Jim Chatelain, John Egner, Bob Sestok, John Piet, Victor Belisle, Michael Luchs, Aris Koutroulis, Bradley Jones, Jerry Hunt, Doug James, and Bill Antonow.

[x] John Egner in telephone conversation with author, 29 July 2000.

[xi] Ibid.

[xii] Jacob, "Kick Out the Jams," 29.

[xiii] Richard Armstrong, "Report from Detroit: Was Cass Corridor a Style?" Art in America (February 1982), 35.

[xiv] John Egner in telephone conversation with author, 29 July 2000.

[xv] Jacob, "Kick Out the Jams," 36, 38.

[xvi] David Elliot, "Detroit Artists Kick Out the Jams, but Where Is the Motown Spirit?" ChicagoSun-Times, 5 July 1981.

[xvii] Armstrong, "Report from Detroit: Was Cass Corridor a Style?"36.

[xviii] Quoted in Barron, "Newton's Universe," 92.

[xix] Miro, "Detroit: The Scrappiness of Survivors." Not all the artists in the Cranbrookexhibition were necessarily included in Miro's characterization. Artists in the exhibition included David Barr, Glenn Booth, Diane Carr, James Chatelain, Naomi Dickerson, John Egner, Steve Foust, Aris Koutroulis, Michael Luchs, Charles McGee, Gordon Newton, Ellen Phelan, John Piet, Melvin Rosas, Paul Schwarz, Robert Sestok, John Slick, Lois Teicher, Adam Thomas, Paul Wesbster, and Robert Wilbert.

[xx] John Egner in telephone conversation with author, 29 July 2000.

Author's Note:

I thank the participants in a planning colloquium for this exhibition, held in January 2000: Joy Hakanson Colby, Sandra Dupret, John Egner, Susanne Hilberry, Mame Jackson, Nancy Jones, Glen Mannisto, Jeffrey Abt, Marsha Miro, Nancy Mitchnick, John Neff, Dennis Nawrocki, Robert Sestok, George Tysh, Robert Wilbert, and MaryAnn Wilkinson.

Dr. Dora Apel received her Ph.D. from the University of Pittsburgh and serves as W. Hawkins Ferry Chair in Modern & Contemporary Art History in the James Pearson Duffy Department of Art and Art History at Wayne State University. Her recent works include Memory Effects: The Holocaust and the Art of Secondary Witnessing (Rutgers University Press, 2002); Imagery of Lynching: Black Men, White Women and the Mob (Rutgers University Press, 2004) and Lynching Photographs, co-authored with Shawn Michelle Smith (University of California Press, 2007).She has also published articles on gender and national identity in visual imagery of the Weimar Republic, Detroit's Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History, Diego Rivera's RCA mural in New York and numerous art and book reviews. Her teaching and research interests include 20th century European and American art, contemporary photography, modernism and postmodern visual culture.

Apel is currently working on two books: You Can't Measure the Sky, a memoir, and The War of Images, on how the meaning of contemporary war is constructed or contested through visual imagery.

Art and the Industrial City is reprinted here with permission of the author. It was first published in the exhibition catalogue Up From the Streets: Detroit Art from the Duffy Warehouse Collection, copyright 2001, Elaine L. Jacob Gallery, Wayne State University. The catalogue, edited by Jeffrey Abt, was published to accompany an exhibition, with the same title, presented at Wayne State University, September through December 2001, in commemoration of the City of Detroit's tricentennial. The exhibition was co-curated by Dennis Alan Nawrocki and MaryAnn Wilkinson.