Selections from the Newton/Duffy Correspondence

Written by Claire Cirocco

Considered to be one of Detroit's most prolific and reclusive artists, Gordon Newton has never faltered in conveying the raw depth of his emotions or the story of his environment through painting, drawing, sculpting, or reconstructing. Newton's contributions to the art world help to define the style of the Cass Corridor movement as well as place it within the larger context of the history of avant-garde art in Detroit and beyond. Newton's work of the past several decades has been described as "dense" and "all-consuming," which can also be applied to the method in which he works. By exhausting ideas and themes and using different approaches to artistic invention over the course of his career, Newton has never failed to generate projects comprised of intricately layered meaning.

Born in Detroit in 1948, Newton experienced the varying landscapes of the Midwest as his family moved from place to place before settling in Port Huron where Newton would attend community college. In 1969 Newton moved to Detroit where he studied at the Society of Arts and Crafts (now the College for Creative Studies) before transferring to Wayne State University. This period of time would mark his initial integration into the Cass Corridor, a scene in which artists sought cheap studio space in the dilapidated buildings that once housed businesses in the area now referred to as Midtown. Around this same time, artists of the movement co-opted a burned-out furniture store at 422 West Willis St., a space that would become the locus of many collaborative projects and exhibitions generated by prominent figures of the scene. The Willis Gallery was not only valued as a raw space in which to create, but played a significant role in networking between artists and potential patrons.[1] Among these collectors and patrons, art enthusiast and proprietor of the Edward W. Duffy & Company pipe supplier James Pearson Duffy emerged as a principal benefactor to preeminent Cass Corridor artists such as Newton, Robert Sestok, and John Egner, providing ample space in the warehouse of his family's pipe supply business in southwest Detroit in which to exhibit art.[2] Duffy took a special interest in the burgeoning art scene, and more specifically, took an interest in Newton's work and the energy he put forth into creating art. Duffy and Newton subsequently began a correspondence, with Duffy's support and patronage acting as catalyst for the propagation of Newton's mail art which would span several decades, from the late 1970s until Duffy's passing in 2009. Newton's exchanges with Duffy (whom Newton often refers to as 'Jim') over the past several decades show an intense involvement and dedication to the creative process on the part of Newton, while simultaneously reflecting the depth of the artist-patron relationship shared between them.

Left: Letter 1 - 1987 - Study for Oliver Twist, marker on paper. Right: Installation view, Oliver Twist: The Old Curiosity Shop, mixed media, 1992. Photo Credit: Tim Thayer.

Though he is often recognized for his role as preeminent patron of the Detroit and Cass Corridor art scene, Duffy held his own artistic vision, which guided his interest in specific artists and their work. Duffy befriended many Wayne State University art students through his frequenting of Detroit galleries from his east side home, linking his social life with his life as a patron of the Detroit art scene. Duffy's own artistic practice reflected his keen aesthetic vision, as he became increasingly interested in photography, and generated hundreds of polaroid photographs documenting his home, art collections and art objects, as well as snapshots from around the city. This enthusiasm and energy with which Duffy collected, documented, and communicated with the art world and artists of Detroit would become the basis for Duffy's initial correspondence with Gordon Newton. Duffy regularly and steadily sent Newton polaroids, each carefully labeled with the exact date and time it was taken. The photographs were often accompanied by receipts, newspaper clippings, and any other objects Duffy felt were necessary to include. Newton describes their correspondence as a "pen pal" relationship. Newton's drawings, photographs, and collages were sent in response to Duffy's initial contact, keeping a steady flow of communication between the two sides, and forming a type of call and response system of reciprocal thought and creative output.[3]

|

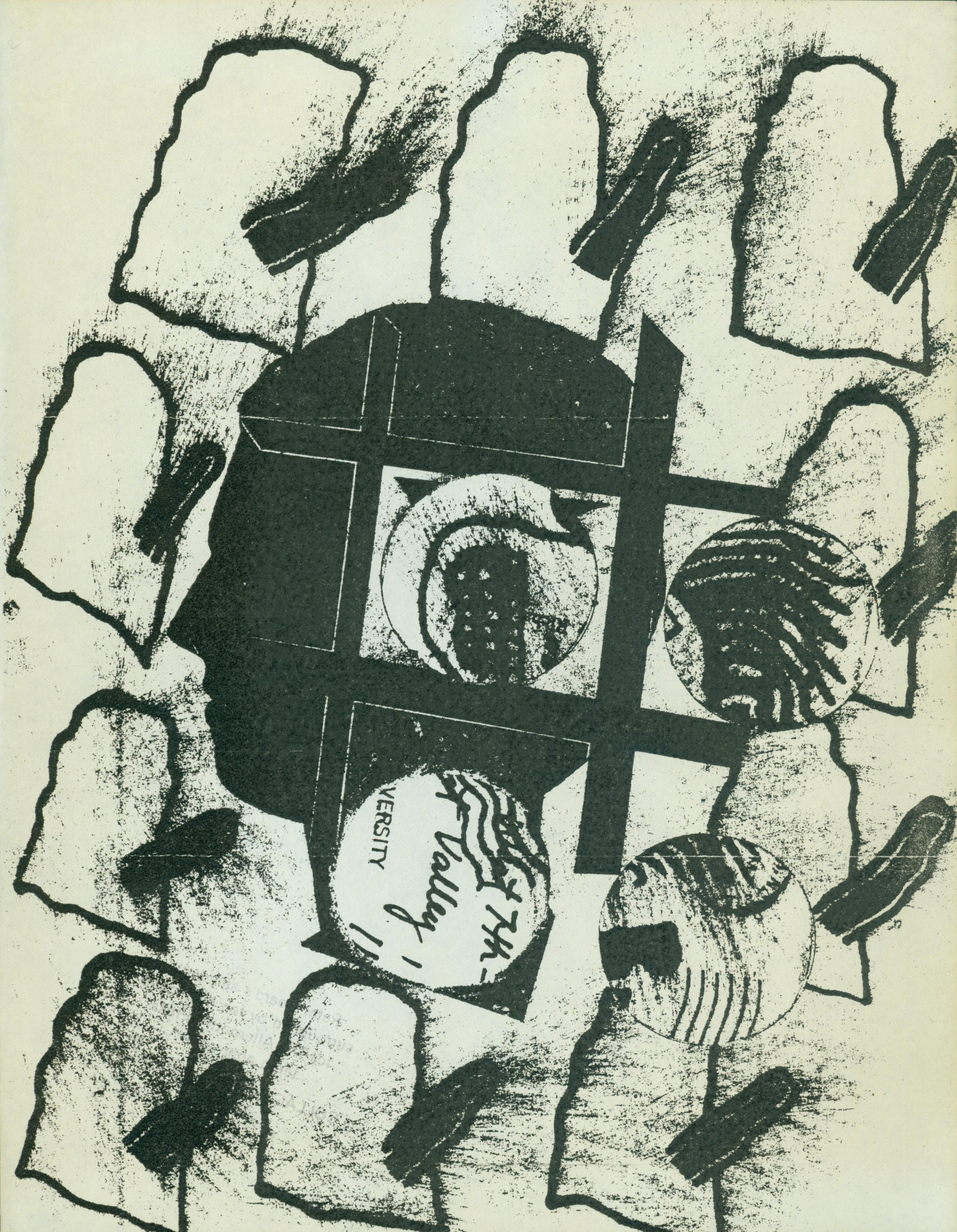

| Peter Beard's Silhouette Surrounded by Ten Michigans for the Alternative Press Tenth Anniversary, collage by Ray Johnson, 1979. Courtesy of Wayne State University Library Systems. |

Upon further study, the hundreds of mailings, accompanied by drawings, sketches, photographs, and collage, can call to mind the mail art of late Detroit-born artist Ray Johnson (b.1927-1995). Johnson is attributed with having established the New York Correspondence School in the early 1960s and the genre of "mail art," a practice involving the accumulation and dispersal of collage and stream of consciousness narratives, often mailed and distributed to a broad network of recipients. Johnson's approach was comparable to a fragmented narrative, accompanied by pieces the artist had been collecting and assembling in collage-form.[4] This pairing of image and word fragments in effect creates multiple layers of meaning, transforming original meanings through varying juxtapositions, essentially mapping the artist's thought process. Johnson would often invite the recipients to participate in the process, by adding or subtracting from the original mailing, and moving the letter on to the next recipient. His method was viewed as a vast departure from the traditional isolation of the artist, producing unique objects that would become commodities for art dealers and collectors.[5] Correspondence implies a personal communication and exchange between sender and receiver, with a special emphasis on the relationship between the two. "I just don't slap things in envelopes," Johnson stated in a 1977 interview with Detroit Artists Monthly, "Everything I make is made for the person I'm writing to."[6]

Newton's mailings encompass elements of Johnson's style and rhetoric, as his energy and penchant for creation is evident in the letters, sketches, postcards, and other media mailed over the years. Newton's techniques of collage and assemblage translate through to his mail art, layering in metaphors and meanings related to tangential ideas producing a "dense," all-consuming mode of artistic expression.[7] Much like Johnson, who once insisted, "That's what these [letters] are all about…I'm trying to depict what goes on in the interior of the head: thoughts, images or ideas," the collection of letters, packages, postcards, sketchbooks, and other ephemera produced during the time of Duffy and Newton's correspondence offers an intimate view into the artist's daily thoughts and processes, as he conveys his practice and artistic vision through a variety of media and careful methods of assemblage.[8] The physical components incorporated into his collage constitute the subject matter, as Newton, establishing his specific perspective of the Cass Corridor aesthetic, uses materials from his own surroundings and everyday life. True of all of his projects, the letters he ritually mailed told the story of his environments, as well as the story of his discovery of the materials.[9]

The body of work produced by Newton, when viewed as a collective whole from the early days of his involvement in the Cass Corridor to the present, noticeably dials in and out of certain themes or usage of subject matter and medium specific to the time at which it was created. These phases vary from heavy use of collage and found-object fragments to sketches and studies for later drawings and sculpture works. These fragments that so often accompanied the letters sent to Duffy function as signifiers of distinct moments in the time of the artist's life, emblematic of both thought and artistic processes that remained salient at the time of their creation.

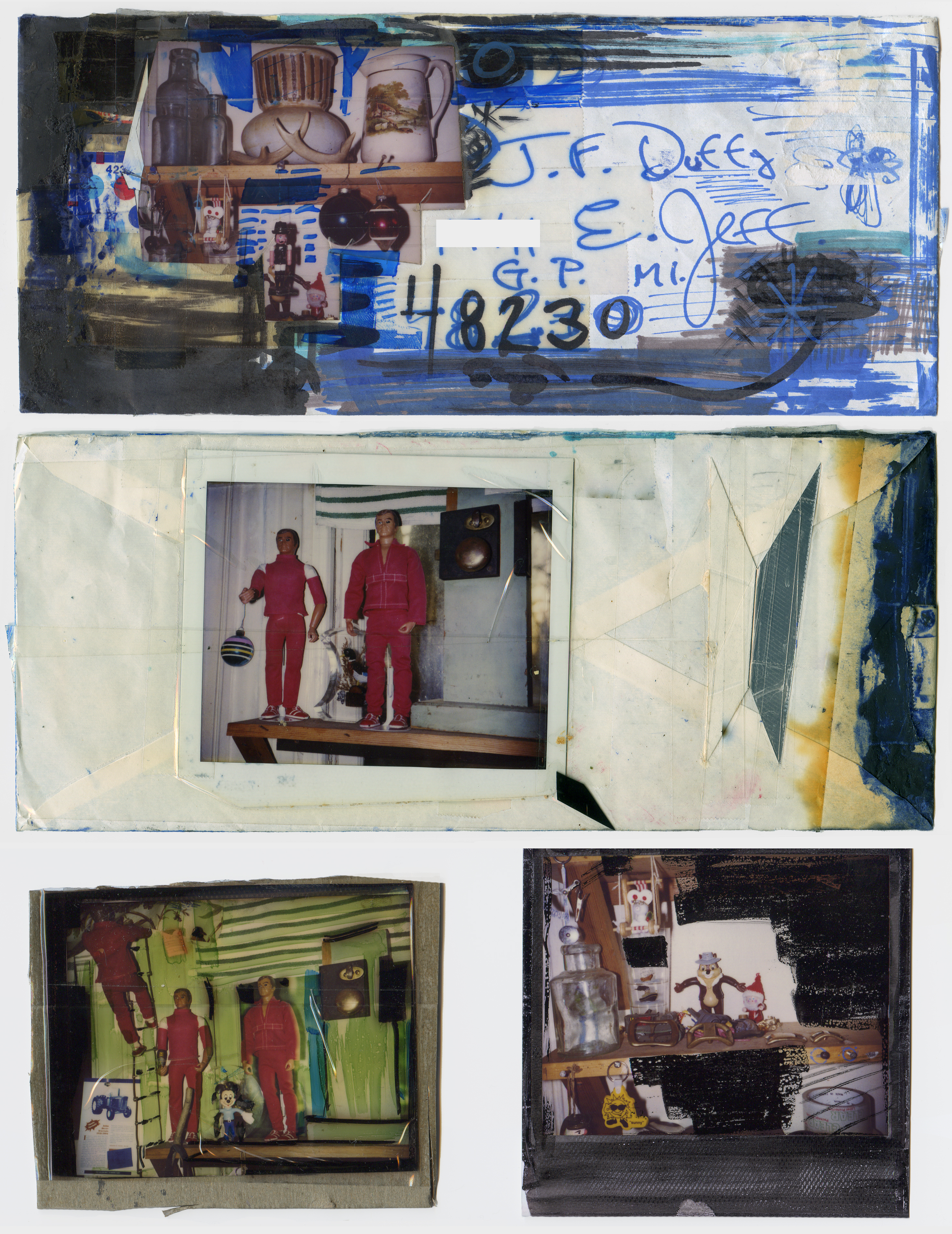

Top: Letter 13 - 1995 marker, tape, scraps on envelope. Bottom: Letter contents, marker, tape, cardboard on photograph, marker on polaroid.

A heavily marked envelope from 1995 inscribed with the name of the recipient "J.F. Duffy" exemplifies the raw energy and intensity imbued in all of Newton's work. The envelope as shown here, and as is true for the entirety of the correspondence, is not merely the vessel for the artist's work, but carries as much significance as its contents. Included in the envelope are two Polaroid photographs taken by the artist and smudged with ink and oil crayon. The photos Newton would include in his envelopes were often still-lifes taken in his home, documenting his surroundings and living/working spatial arrangements. The decorative elements of the artist's home thus become those of the letter itself. The mixture of media again highlights the method of densely layering the structured image with free-form sketches.

|

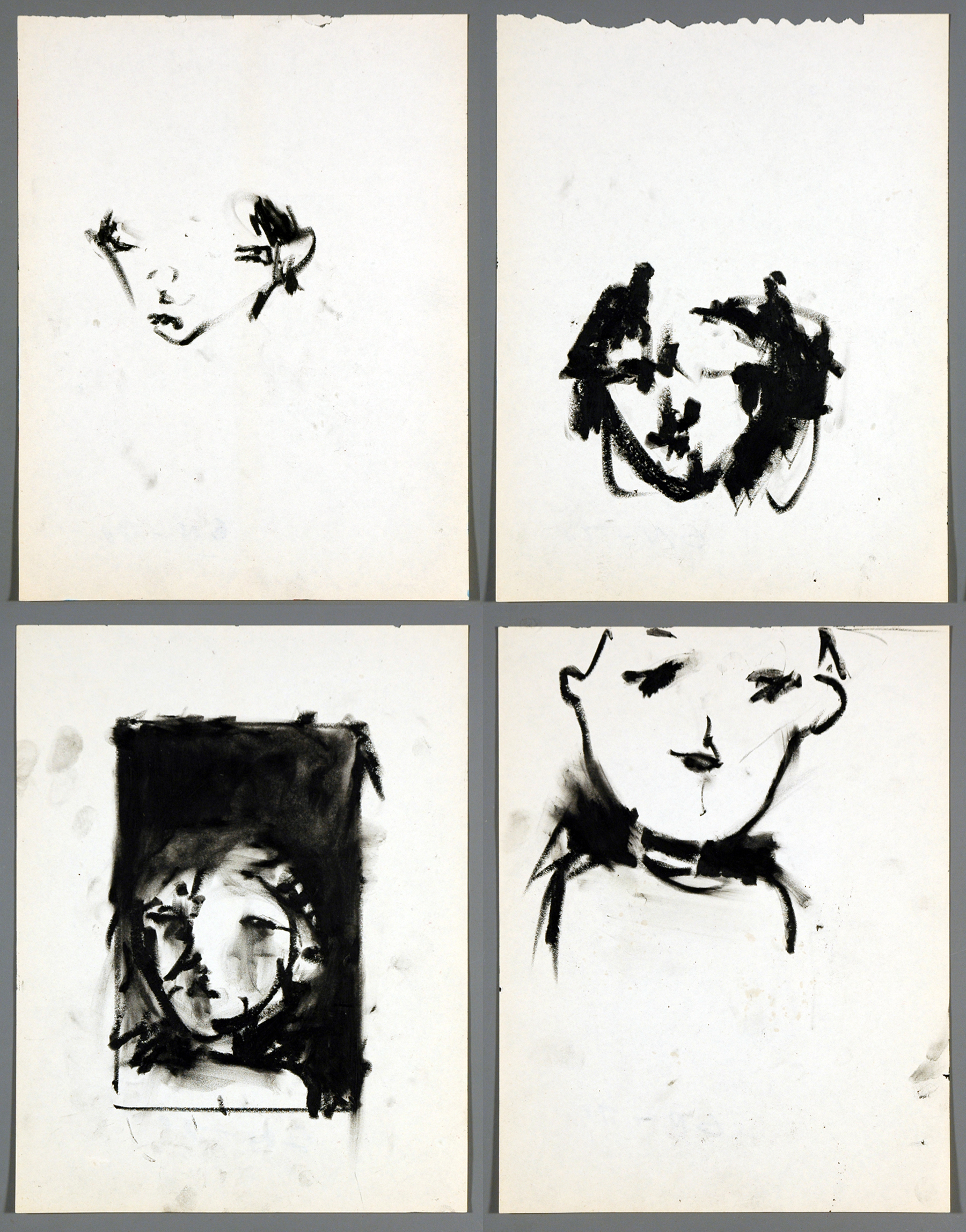

| Letter 1 - 1999 contents: charcoal, pastel, pen on paper. |

An oversized envelope from 1999 includes 4 oil-stick drawings on newsprint dated 1971, and a smaller-scale sketch inscribed on the back of a jaggedly-cut, repurposed postcard. This later example, though visually much simpler and less chaotic, still bears Newton's characteristic pencil and ink drawings, with simplistic figural representations done in a seemingly abrupt fashion. This was a key aspect, not only of Newton's mail art, but his sculpture as well. Fellow Cass Corridor artist John Egner commented on this facet of the sculpture, saying that every incision and application by Newton's hand was precise and deliberate.[10] What appears a result of chance or accidental happening is conversely the careful choice of the artist. Smudges of charcoal and streaks of oil pastel coalesce to represent delicate portraits and opaque figural studies of densely-packed coiled lines. Each of the hundreds of envelopes and packages received by Duffy contained not simply letters, but photographs, sketches, notebooks, journals, grocery lists, newspaper clippings chronicling the day and year of their mailing, watercolor and gouache paintings, mixed-media collages, sculpture studies, food labels, coupons, and other various ephemera.

The catalogued correspondence, in its entirety, is monumental. From the early years of Newton's career as an artist to the near-present, the Newton/Duffy Correspondence continues to represent an integral insight within the University Art Collection, and stands as a true testament of time through the eyes of Newton. The thousands of pieces acquired by Duffy over the past forty years offer a wealth of evidence and information on the cultural significance of Detroit artists and the Cass Corridor artists' movement. An even closer examination of these materials is yet to be conducted, as the work of archiving this vast collection coupled with the brevity of this initial overview does not delve into the great depths of this body of work. This collection of personal works documenting the life of Newton may ultimately shed light on one of Detroit's great forerunners of the avant-garde.

I would like to extend special thanks to Gordon Newton for his enthusiasm for this project and his generous participation; to James Pearson Duffy (1923-2009) for his outstanding bequest to the WSU Art Collection; to Andrew Camden and Ed Fraga for the care they demonstrated in administering the Duffy Estate and to the Detroit Institute of Arts for their support of this project.

Many others dedicated their time and effort in helping preserve, document and share this remarkable group. Funded through the support of College of Fine, Performing and Communication Arts, Dean's Office Activity Awards, undergraduate students Isaac Pool transformed shoeboxes of materials into chronologically organized and archivally preserved files and Devon Parrot spent endless hours imaging and cataloguing thousands of objects. Collections Assistant, Daniel Sperry, created the exhibition design and championed this effort from the start. I would also like to thank WSU Library System's Special Collections Coordinator and History Librarian, Cindy Krolikowski, for her assistance in providing the Ray Johnson piece.

Lastly, I would like to acknowledge Claire Cirocco, the collection's talented 2014/15 Activity Award student, who contributed the thoughtful and articulate essay created for this exhibition.

Sandra Schemske, Art Collection Coordinator, Wayne State University

[1] Mary Jane Jacob, "Kick Out the Jams: The Emergence of a Detroit Avant-Garde," In Kick Out the Jams: Detroit's Cass Corridor 1963-1977. (Detroit: The Detroit Institute of Arts, 1980).

[2] MaryAnn Wilkinson, "'We Put Art Anywhere and Everywhere We Can': The Duffy Company Warehouse," In Up From The Streets: Detroit Art From the Duffy Warehouse Collection, edited by Jeffrey Abt.(Detroit: Elaine Jacob Gallery, Wayne State University, 2001), 28-29.

[3] Gordon Newton, in discussion with the author, March 22, 2015.

[4] Michael Morris, "Ray Johnson: An Appreciation," In Ray Johnson: How Sad I Am Today… edited by Michael Morris and Sharla Sava. (Vancouver: Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, University of British Columbia, 2001), 7-10.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ray Johnson, interview by Diane Spodarek and Randy Delbeke, The Detroit Artists Monthly, (February 1978).

[7] Marsha Miro, "Gordon Newton: Thirty Years Later," In Gordon Newton: Selections from the James F. Duffy, Jr. Gift, edited by Judith Ruskin. (Detroit: The Detroit Institute of Arts, 2001), 8-20.

[8] Johnson.

[9] Ruth Rattner, "Gordon Newton," Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts 58, no. 1 (1980).

[10] 'Images' from Detroit's Cass Corridor. By Kathryn Brackett-Luchs and Shaun Bangert. DVD.

All images copyright the artist, and may not be reproduced without written permission. Gordon Newton works reproduced with the artist's permission