William Gropper: The Capriccios Suite

Written by Catherine Milewski

From his humble beginnings in the tenements of New York's Lower East Side to his artistic radicalism and subsequent blacklisting by Senator Joseph McCarthy, William Gropper (1897 1977) always stayed true to his vision for exposing the realities and struggles of the daily life of the lower class. Known to some as the "American Daumier," Gropper's involvement with radical press like The Daily Worker and The New Masses caught the attention of McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee, and his investigation in 1953 inspired his incredible series of fifty lithographs, The Capriccios. Gropper's tenacity and strength of depiction are culminated in these lithographs, which expose the fallacies of mid-century America during a time of great turmoil and suspicion.

Born in 1897 in New York's Lower East Side to two Eastern European Jewish immigrants, Gropper saw firsthand the struggle faced by many poor families in his neighborhood. His father, Harry Gropper, came from Romania fluent in eight languages and educated at several universities in Europe yet was still unable to acquire a job better than working for low pay at a garment factory.[1] His mother Jenny was so occupied with providing for her family by sewing and working in the garment district that Gropper felt that "…the sweatshop kept us alive, but robbed us of our mother."[2]

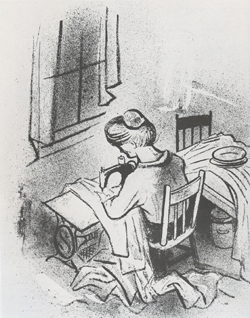

|

| Biographical illustration of Gropper's mother at her sewing machine. 1925. Ink. 12.5 x 9.5 in. Photo: Geoffrey Clements. |

In his early biographical cartoons, Gropper depicts his mother bent over her sewing machine completely lost within her work, a Whistler-esque tribute to her amaranthine dedication. Growing up in a rigid educational system in addition to witnessing the laborious struggle endured by his parents and the negligent death of his aunt in the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire bred contempt within Gropper for exploitative business practices and institutions.[3] The establishment of the Ferrer School, an anti-clericalist art school near Gropper's home would become the first step towards Gropper's artistic career.

The semi-radical Ferrer School was more than just a school of the arts it was a platform for experimentation in philosophy, civil rights, socialism, and any other idea that veered from the norms of society. By a chance meeting with a member of the school, at age thirteen Gropper was invited to attend courses and study with artists who would become his most prominent influences Robert Henri, George Bellows, Man Ray, and William Glackens.[4] The lectures given by Henri on "art for the people" and a new focus on American realism (slums, poverty, and urban decay) sparked the already burgeoning interest of Gropper, whose firsthand views of American impoverishment fueled his artistic furor. His talents brought him to the attention of Frank Alvah Parsons, president of the New York School of Fine and Applied Arts (now Parsons School of Design), who offered him a full scholarship. Gropper's association with the school would bring him to work with the New York Tribune in 1917, and later as a war poster artist for the Creel Committee on Public Information.[5]

Working for a government agency was a lucrative position, but it revealed to Gropper even more of the social injustice that he despised. His position within the company allowed him to avoid the draft for World War I, but made clear the dividing line between the poor dying for the rich and the rich raking in war profits. As the Tribune was one of the leading newspapers in "anti-red hysteria," the paper sent a reporter accompanied by Gropper to investigate the Industrial Workers of the World main office and deliver scandalous tales of leftist schemes.[6] Unfortunately for the Tribune, Gropper and the reporter were charmed by the revolutionary ideas of the IWW, and Gropper himself was "let go" by the newspaper for his new involvement with the radical publication of the IWW, the Rebel Worker. Thus began his foray into the world of revolutionary cartoons, political satire, and exposés of injustice.

|

| From the Watergate Series, #8. 1973. Color lithograph. 22 x 30 in. Gift of Miriam Feldman. |

Gropper's style developed into its unique technique during his time working with monthly socialist magazine The Liberator, and his accomplishments were not going unnoticed. Simultaneously, Gropper worked as an editor for The Liberator, contributed to the Dial, drew for the Communist-affiliated Yiddish newspaper Freiheit, and helped found Marxist magazine New Masses.[7] In addition to all his work with leftist movements, the Soviet Union invited him as a guest of honor for the tenth anniversary of the state. Life seemed to be going well for Gropper; he was drawing for more mainstream publications like Esquire, the New York Post, and Vanity Fair, the latter collaboration resulting in the offending of the emperor of Japan, Hirohito, and the subsequent forced apology by the American press. The 1935 drawing in question, a caricature of Emperor Hirohito pulling the Nobel Peace Prize along behind him on a cart, caused international uproar and amusement, with Gropper himself smugly stating that then-Secretary of State, Cordell Hull, "… can apologize all he wants to; I shall continue my work."[8]

|

| Construction of the Dam, Mural for the Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C. 1937. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. |

|

| Automobile Industry Mural, Detroit Post Office. 1940. Long-term loan from the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Photo by Daniel Sperry. |

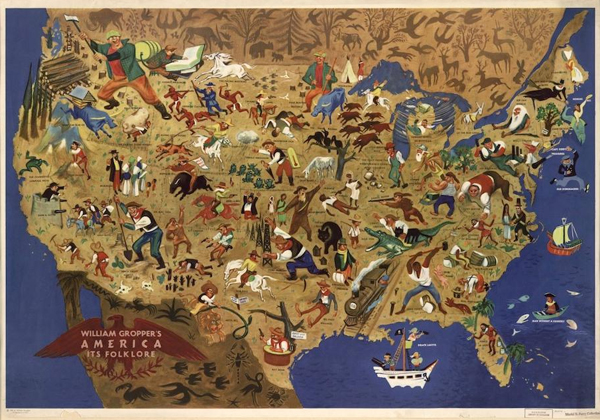

Gropper's brand of social commentary was on its way to mainstream popularity, with commissions coming in for murals in the Department of the Interior Building in Washington in 1937 and the Automobile Industry mural for Detroit's Post Office in 1940, but not everyone would agree with his participation and collaboration with radical leftist groups.[9] In 1942 the Federal Bureau of Investigations began maintaining a file on Gropper, alerted by his work with the New Masses and The Daily Worker. While Gropper continued to produce his biting, satirical sketches and cartoons for popular publications, it was the creation of something else, something benign that set off the FBI's radar Gropper's America: Its Folklore map.

|

| America: Its Folklore map of the United States. 1946. Lithographic print. 22.5 x 32.6 in. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress. |

Gropper's 1946 pictorial map of the various folktales and folk characters that originated in different American territories sparked the interest of Senator Joseph McCarthy's blood-thirsty committee, who assumed its distribution to American information offices overseas held a connection with Communist spies abroad.[10] Brought before a tribunal held by McCarthy's committee in 1953, Gropper had prepared a statement about his work involving the map and his artistic affiliations with radical publications but was barred from expressing his personal thoughts.[11] As Gropper observed the corrupt nature of Senator McCarthy and his cronies, he chose to protect his coworkers as well as himself by pleading the Fifth Amendment and refusing to speak. This action displeased the committee, and as a result Gropper's life would change drastically both artistically and personally. Gropper's telephone was tapped by the government; the FBI harassed him, his family, and anyone involved with him professionally; Gropper was unable to sell his house, procure a loan, or rent another property due to a restriction placed upon his person by the government. In addition to this mistreatment, Gropper also became the first of only two artists to be "blacklisted" by the American government.[12]

Gropper's blacklisting was detrimental to his artistic career; galleries stopped hosting exhibitions of his art, his cartoons were condemned by the public, and his work was shunned. Gropper worked to make ends meet, but his blacklisting in conjunction with the rising popularity of abstract art made it difficult to remain an artistic presence however, an incident in Detroit would rekindle Gropper's fire and solidify him as one of the most prolific political satirists of the 20th century. The Cranbrook Academy of Art had scheduled an exhibition of Gropper's work within one of their galleries as well as a lecture by the artist, but when Gropper and his wife arrived in Detroit they were greeted by the news that both show and lecture had been cancelled due to his blacklisting. Enraged, Gropper made arrangements for the show and his lecture to be moved to a private home, where the rooms overflowed with supporters. Gropper applauded the large audience for attending, and denounced Cranbrook for complying and conceding to the "scare tactics" of the American press.[13] When a voice from the back of the room asked Gropper what he would do to counter the press, Gropper shouted "I will do a caprichos à la Goya!" and the famed Capriccios series was set into motion.[14] Fueled by donations and pledges from twelve of the lecture attendees, Gropper went on for the next three years to produce his fifty-print set, the Capriccios.

|  |

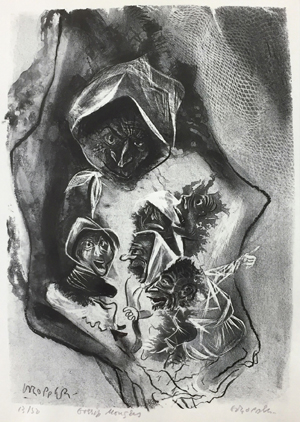

| Francisco de Goya, Soplones (Tale-Bearers - Blasts of Wind), Number 48 from the series Los Caprichos. 1797-98. Etching and aquatint. 7.5 x 5 in. Wayne State University Art Collection Purchase, 2012. Photo by Daniel Sperry. | Gossip Mongers from the series The Capriccios. 1953-56. Lithograph. 16 1/2 x 12 5/8 in. Gift of Arthur Schwartz. Photo by Daniel Sperry. |

Francisco Goya's own Los Caprichos, a set of eighty aquatint and etching prints (1797-9), explore themes of declining rationality in the face of superstition, injustice, and political satire. Greatly inspired by Goya's other works in addition to his Caprichos, Gropper's version reflects many of the same themes: Goya's condemnation of the Spanish Inquisition is mirrored in Gropper's denouncement of the "American Inquisition" McCarthy's witch-hunts and the harassments of the House Un-American Activities Committee. Like his political cartoons, Gropper uses scale to delineate shifts of power between characters within his Capriccios, such as in The Haves and the Have Nots, where a towering figure reminiscent of Henry VIII looms over the shriveled figures of the poverty-stricken populace. But unlike within his cartoons, the characters themselves are not always so obvious contemplation is required to understand the full spectrum of the narrative. In Gossip Mongers, Gropper portrays the spread of condemning information in the form of a group of old crones, spreading vicious lies and scandalous falsities. Gropper's suffering at the hands of the gossip of the popular press is expressed within Gossip Mongers, and he himself called the industry a place "…where fools gather for their mutual destruction."[15] Much like Goya's critical views of the Spanish public's reliance on superstition, Gropper saw political informers (such as his own accuser, Harvey Matusow, who later recanted his testimony) and the fearful society as evidence of America's growing ignorance and ineptitude.

|  |

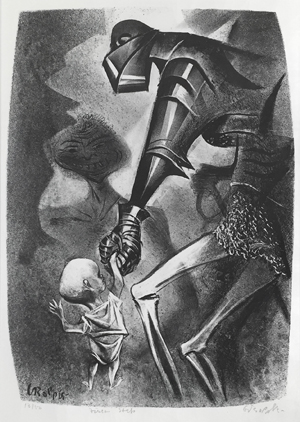

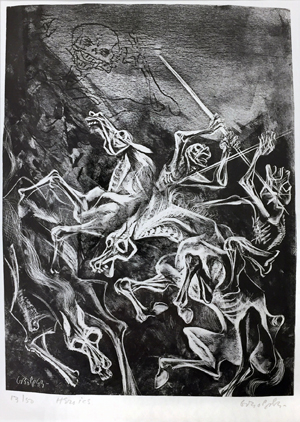

| First Step from the series The Capriccios. 1953-56. Lithograph. 16 1/2 x 12 5/8 in. Gift of Arthur Schwartz. Photo by Daniel Sperry. | Heroics from the series The Capriccios. 1953-56. Lithograph. 16 1/2 x 12 5/8 in. Gift of Arthur Schwartz. Photo by Daniel Sperry. |

Other prints from the Capriccios set are multi-faceted. First Step shows a knight armored from the waist up from the waist down, he appears skeletal. Taking a small child by the hand, he appears to lead the child towards a ghostly, sinister figure in the background to where? Will the child be lead to a life of warfare, or a life of revolution? Gropper intimates that either is possible. In these prints, reality is suspended in favor of dynamism. In addition to scale differences, people seem to float, fly, leap, and fall out of the picture plane. Heroics shows a wild, skeletal horseman charging amidst a whirlwind of specters and shades. The chilling cavalry of the living dead are engaged in a battle, with their horses tumbling over themselves as a mirage of a bony overlord looms in the background. The sense of weightlessness and lack of gravity increase the urgency and furor of conflict. Black List, a piece exploring the aftermath of his own blacklisting, shows a tangle of bodies wrapped up in powerful strokes of black ink, subdued by government control as emotionless bystanders watch. The diagonal composition and flurry of trapped souls and their entanglement could represent how Gropper felt after his condemnation by McCarthy's committee unfairly silenced, trapped under the black lines synonymous with redaction.

Gropper's furious creation of his Capriccios was mirrored by the whirlwind of cultural tension felt in the United States in the mid-20th century. Just as quickly as it was ignited, the strain of the Red Scare dissipated and Gropper's reputation resurfaced. After his tour de force of the Capriccios, Gropper turned his attention towards criticizing the highly-politicized art scene that had abandoned him in the wake of his blacklisting. As a lingering result of his blacklisting, Gropper was barred from major exhibitions in New York until 1961.[16]

|

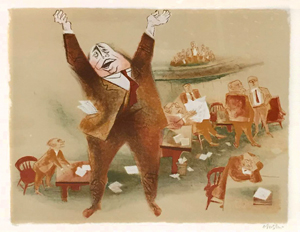

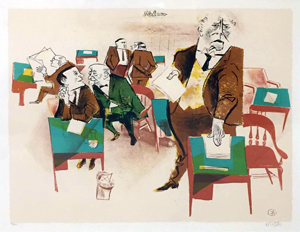

| From the Watergate Series, #4. 1973. Color lithograph. 22 x 30 in. Gift of Miriam Feldman. |

In 1973, Gropper created a series of ten color lithographs of political events surrounding President Nixon's Watergate scandal, marking the return of the artist to political satire. Gropper's work was continuous up until his death in 1977. Gropper's commentary of the political climate of post-World War II America resonated deeply with those involved: his art enlivened the overworked and underprivileged public and enraged the corrupt, domineering politicians who sought to subdue his work and others like it. His mark upon history sheds light upon a dark time in America and his struggle against corruption, as illustrated in his Capriccios, truly has earned him the nickname "The American Daumier."

[1] Gahn, J. The America of William Gropper, Radical Cartoonist. (PhD. diss. Syracuse University, 1966) 5-6.

[2] Ibid., 10.

[3] Lozowick, L. William Gropper. (Philadelphia: Art Alliance, 1983). 23.

[4] Gahn, The America of William Gropper, 18.

[5] Ibid., 26.

[6] Lozowick, William Gropper, 26-27.

[7] Gahn, The America of William Gropper, Radical Cartoonist, 38.

[8] Lozowick, William Gropper, 34.

[9] Currently, Gropper's restored Automobile Industry mural is on display on the second floor of the Wayne State University Student Center.

[10] Ibid., 53.

[11] Gahn, The America of William Gropper, Radical Cartoonist, 284-5.

[12] The second, Rockwell Kent, had his passport revoked and was blacklisted in 1955.

[13] Steinberg, N.S. William Gropper's "Capriccios". (Print Quarterly Publications, 1994) 1.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Steinberg, William Gropper's "Capriccios", 33.

[16] Lozowick, William Gropper, 71.